I am not so arrogant as to think the universe has singled me out to teach me a lesson, but there are times when the plot twists are so perplexing that it would be arrogant not to search for one. In the last two months, four people close to me have left the world as I know it. Until now, I had been mostly fortunate to have avoided the harsh realities of mortality, but as the saying goes, when it rains, it dumps an ocean on your unsuspecting ass. I feel as if my very foundation has been swept away, flooded with new possibilities of finiteness, loss, compassion, regret. Stories in the news of someone dying are no longer abstract. The connection with someone who has also lost a parent is palpable, a calling card of uninvited, unrelenting wisdom. Petty concerns are infuriating, confusing, and altogether the perfect distraction when the pain and uncertainty is just too much. My reality is both more empty and more full. A paradox of better understanding the nature of the universe and coming to terms with the fact that it makes no sense.

I think most of us are born with, or adopt or are taught, the delusion of permanence. Our parents will always be there — we have to believe this because if not, we will die. Even if that’s not entirely true, it’s how we feel. They are the source of life, of security, of happiness, and coming to terms with their human-ness is hard enough, not to mention their mortality. I always knew intellectually that losing a parent was a rite of passage of sorts, something impossible to truly understand until it happens. The loss of a friend, particularly someone who showed no signs of sickness or even weakness, someone who loved life and loved his friends, is another puzzle that can only be solved once the pieces are in front of you, if at all. Even the passing of someone who fought in wars decades before you were born is a shock, because somehow once someone has lived to the ripe old age of 96, they appear eternal. I suppose it feels as if we will all live forever, until we don’t. Death is something impossible to grok until you face it, and by then it’s too late. And those of us who are left to witness the impermanence of our loved ones, our heroes, and even our enemies, can only honor that loss by questioning the very purpose of this absurd and beautiful opportunity called existence.

Even the youngest of Tibetan monks learn to meditate intensely on death and impermanence. Although they believe in an afterlife, the uncertainty of what form that will take gives added weight to the importance of the human experience and living a meaningful life. While it's impossible to know what comes next, I find it practical to hedge my bets. In other words, if there is an afterlife, I hope I will have done enough good in the world to have earned a good rebirth; and if there isn’t, well then I hope I did enough good in the world to have left the place a little better than how I found it. All I know is that my soul, or whatever “stuff” I’m made of, has the opportunity to experience life now — in all its confusing, complex, painful, and messy magnificence. I was sharing with a friend recently that I was feeling guilty that my dad might have waited for me before he finally passed, that I had participated in prolonging his pain. He fought so hard for every breath, just as he had fought so hard for everything in his life, and never, never complained. My friend replied, “life is pain.” And it’s true. Why would I want to take that away? We shouldn’t shun the pain. It’s how we know we’re alive. We simply have to learn to be with the pain, to not be afraid of it, and to embrace both the emotional pain of loss and the physical pain of pushing against our boundaries. Pain is training to live, comfort is… well… the opposite.

There came a tipping point for me, in the midst of a cycle of sorrow I thought I might never climb out of, when I realized the source of much of my suffering was the unwillingness to accept uncertainty. My whole life I’ve been trying to control, to predict, to keep myself safe — from harm, from making mistakes, from losing people I love — but it’s a rigged game. There is no possibility of controlling these things and there are no winners when you try. Getting what you want only reinforces the delusion that it’s possible to control and that our attachments are worth using all our energy to keep. Targets are good, don’t get me wrong, but in the end, it’s not hitting the targets that matter, it’s the number of arrows you've shot. If you spend too much time waiting, lining up your shot, worrying that you might miss, you will most certainly miss the most important thing of all — you. I’ve realized now that instead of hitting a bullseye, I’d much rather have the target, and everything surrounding it, covered in arrows, broken, backwards, buried. Who knows? I might hit a target I didn’t even see! Didn’t Schopenhauer call that genius? Whether it’s the wind that carries it astray, my own poor aim, or someone else’s arrow, it doesn’t matter. What matters is that we shoot. What matters is that we try. There is so little we can really control, perhaps nothing beyond our own experience, and even that would be debated by Pavlov.

So maybe it’s not so much a lesson I’m looking for as it is a new way of moving through the world. Paying attention to the details but not getting lost in them. Caring about what people feel, not what they think. Doing things today that can be done tomorrow. Striving for the things that matter to me, not what’s written in my programming. Having the self-awareness to question even my strongest beliefs as well as the humility to change them. Facing adversity with vulnerability and compassion, for I am not alone in my fear, but if I run away, I will be. Death, I guess you could say, has planted the seeds to understanding the nature of aliveness. All I can do is water them with my tears and hope that from the darkest shade will grow the most beautiful garden, which one day too will die, making it all the more precious and alive.

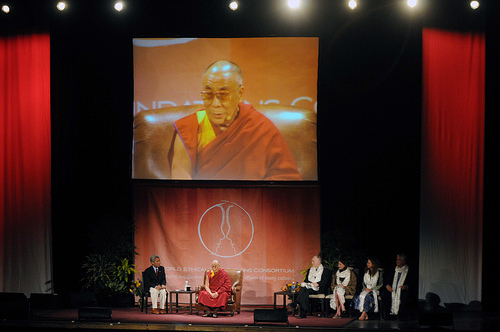

Recently I had the rare privilege of meeting His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama and listening to his public address on “Compassionate Ethics in Difficult Times.” The significance and meaning of such an honor is still settling in, but I would like to express a few thoughts on my experience in the meantime. Obviously, I was incredibly moved and left with many a concept to ponder, but as I listened to him speak, I saw a man who not only has a remarkable understanding of the human condition and capacity for compassion, but who embraces every atom of this experience we call being human. His humbleness and his ability to express a genuine love for all human beings is awe-inspiring.

Recently I had the rare privilege of meeting His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama and listening to his public address on “Compassionate Ethics in Difficult Times.” The significance and meaning of such an honor is still settling in, but I would like to express a few thoughts on my experience in the meantime. Obviously, I was incredibly moved and left with many a concept to ponder, but as I listened to him speak, I saw a man who not only has a remarkable understanding of the human condition and capacity for compassion, but who embraces every atom of this experience we call being human. His humbleness and his ability to express a genuine love for all human beings is awe-inspiring.